“THERE is only one chief! One commander! One authority!” These thunderous assertions came from Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s president, during a recent television appearance. Oddly, he was not talking about himself. He was extolling the defence minister, Vladimir Padrino López (pictured with Mr Maduro), who nodded appreciatively. The general, long a behind-the-scenes operator, has become much more visible and powerful.

In July Mr Maduro put him in charge of the government’s latest effort to alleviate food shortages, which have destroyed the populist regime’s prestige and threaten its survival. Things are now so bad that McDonald’s has stopped selling Big Macs because it cannot get the buns (a privation for the few Venezuelans who can afford them). The “Great Mission of Sovereign Supply” takes the bulk of food distribution away from an array of state and privately owned wholesalers and entrusts it to the army. General Padrino López, whose first family name means “godfather”, would be answerable to no one, Mr Maduro proclaimed. “All ministries and government institutions [involved in distributing food] are subordinated” to him. Mr Maduro told the army to take over the ports, too.

In this section- Army rations

- Defendant-in-chief

- Weeds of peace

One big question is whether General Padrino López is now also in charge of Mr Maduro, or soon will be. The president has “transferred power”, believes Cliver Alcalá, a retired major-general who counts himself an admirer of General Padrino López. Writing on Latin America Goes Global, a website, analysts Javier Corrales and Franz von Bergen contend that Venezuela may have undergone “a new type of coup” in which “the president is not displaced, but effectively handcuffed.”

The regime was already a quasi-military one. Its founder, Hugo Chávez, was an army colonel who once attempted to stage a coup (he failed, but later won power in an election). His government was a civil-military union, in which the army acted as a spearhead of his “Bolivarian revolution”. The hapless Mr Maduro, chosen by Chávez to be his heir before he died in 2013, is a civilian and can look awkward at military gatherings. But he has kept the government’s martial tone. A third of his ministers are soldiers. Following a failed coup attempt in 2002, Chávez asserted full control over the army; after he died it resumed its historical role as an arbiter of power.

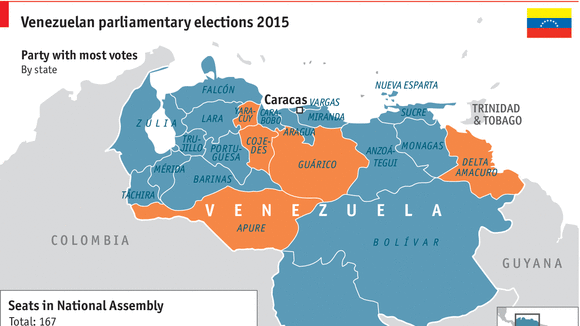

That became apparent after Venezuela’s parliamentary election on December 6th, when the opposition won control of the national assembly for the first time in 17 years. After the vote General Padrino López went on television to congratulate citizens for taking part in a peaceful democratic process. Some analysts interpreted this as a warning to Mr Maduro not to reject the opposition’s victory. More recently, General Padrino López has spoken of a “failure of governance”. There is no reason to doubt his loyalty to Chávez’s revolution; to defend it, he might betray the president.

The army’s future role may now be intertwined with the opposition’s attempt to unseat Mr Maduro by holding a recall referendum. On August 1st the election commission confirmed that the opposition had collected enough signatures to move to the second stage of the recall process: the collection of signatures representing at least a fifth of the electorate—about 4m. If Mr Maduro’s foes achieve that, by law a referendum on whether to oust him must be held. Since less than a quarter of Venezuelans approve of his job performance, he would probably lose.

Recall to duty?

Timing is everything. If Mr Maduro is ejected before January 10th there will be a new presidential election; if after, the vice-president, currently Aristóbulo Istúriz, will take over. In that case, General Padrino López might increase his influence over government still further.

By then, though, the army’s already diminished prestige may have suffered from its failure to alleviate food shortages. The government blames them on black marketeers, whom the army is to evict from the distribution network. This is delusional.

The shortages are caused by price controls, which make it illegal to sell essential goods for more than a fraction of what they cost to make. Domestic production of everything from bread to toilet paper has predictably plunged. Thanks to low oil prices and its own incompetence, the government does not have enough money to subsidise imports to make up the shortfall. The black market is a consequence, not the cause, of shortages. Reaffirming his rejection of economic reality, Mr Maduro appointed a new commerce minister who last year praised the Soviet Union as a “highly self-sustaining country”.

Soldiers are unlikely to help much. Military checkpoints on the border with Colombia already skim off cash from smuggling networks. On August 1st a court in New York charged Néstor Reverol, an ex-commander of the national guard and Venezuela’s former drug tsar, with cocaine trafficking. The day after the indictment Mr Maduro named him interior minister.

There is little evidence that the Grand Supply Mission, inaugurated on July 11th, is making much difference. Venezuelans still spend hours queuing at supermarkets with empty shelves. Millions are desperate for bread. Perhaps the generals will manage to put the buns back on Big Macs. More likely, they will demonstrate that supply and demand, unlike soldiers on parade, do not follow orders.

From the print edition: The Americas